The Celtic Tiger’s Legacy: Exploring FDI-Driven Growth and Housing Market Challenges in Ireland

Abstract

This analysis explores the intricate relationship between Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), employment, and housing market dynamics in Ireland, a country that has transitioned from protectionism to a globally integrated economy over the past century. FDI has been a cornerstone of Ireland's economic growth, particularly during the Celtic Tiger era, attracting multinational corporations in sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, and finance. However, this influx has intensified housing demand, particularly in urban centers like Dublin, where housing supply remains constrained due to bureaucratic inefficiencies, restrictive land-use policies, and limited public housing investments. The paper examines historical trends in FDI and housing prices, highlighting the impact of employment growth on housing demand and affordability. It also evaluates existing policies, such as Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs) and public-private housing partnerships (PPPs), proposing enhancements to improve their effectiveness. Recommendations include streamlining planning processes, expanding public transportation networks and promoting regional economic development to reduce the concentration of demand in urban hubs. The future outlook discusses the implications of global tax reforms, sectoral transitions, climate goals, and technological advancements, emphasizing the need for coordinated policies to ensure sustainable and inclusive growth. Ireland's experience offers valuable lessons for other small, open economies navigating the interplay between FDI-driven growth and housing market pressures.

History of FDI and Housing Prices in Ireland

Ireland’s economic trajectory has evolved significantly over the past century, transitioning from protectionism to a globally integrated, export-oriented economy. The epoch of economic nationalism initiated by Eamon de Valera sought self-sufficiency, marked by high tariff rates under the 1932 Finance and Control of Manufacturers Acts, which required majority Irish ownership of new manufacturing ventures. However, this approach led to economic stagnation by the 1950s. A pivotal shift occurred in the mid-20th century which introduced export profit tax relief to incentivise manufacturing exports, and, by the late 1950s, Ireland had joined the World Bank and IMF, relaxed protectionist policies and embraced FDI. Further trade liberalisation led to Ireland’s subsequent joining in the GATT in 1967. In the 1980s, economic challenges––including high debt and unemployment––prompted structural reforms and the Program for National Recovery (PNR) in 1987, which emphasised pay restraint and fiscal discipline to boost competitiveness. The 1990s marked Ireland’s transformation into the Celtic Tiger, with favourable tax policies, and a skilled workforce. These factors attracted unprecedented levels of FDI, particularly from American ICT and pharmaceutical companies. Investments in education, infrastructure, and innovation reinforced investor confidence. The establishment of IDA Ireland and Enterprise Ireland in 1994 streamlined efforts to attract FDI while nurturing indigenous businesses, further solidifying Ireland's position in the global economy. With regards to national housing prices, Ireland has experienced significant fluctuations over the past few decades. During the Celtic Tiger era, the first wave of property price inflation soared due to rapid economic growth, speculative investments, and loose lending policies. The 2008 global financial crisis caused a dramatic collapse, with housing prices falling by nearly 50% from their peak, leaving behind unfinished developments and “ghost estates. ” Recovery began around 2013, driven by economic growth, but the supply of new housing remained constrained, causing prices to steadily rise. By 2021, housing prices had surpassed their pre-crisis peak.

Urbanization, Employment, and Housing Market Dynamics in Ireland

Urban clusters lie at the core of modern economies, with cities accounting for fewer than 1% of global land use, but the large majority of global economic activity. Concentrated agglomerations foster labor market specialization, cost savings, knowledge spillovers, and numerous other secondary benefits. The concept of the bid-rent gradient is fundamental to understanding urban economics, as it reflects the opportunity cost of distance from city centers. Urban centers derive their value from both consumption and labor market amenities, with recent analyses often emphasizing the growth of consumption amenities (e.g., Glaeser et al., 2001). However, employment arguably remains the most significant value factor a location can offer. As previously mentioned, the property price inflation before 2008 was significantly driven by speculative investments and loose lending practices, which distorted the housing market. Following the financial crisis, stricter regulations were introduced, reducing speculative behavior and creating a more stable and transparent housing market. This post-crisis regulatory environment provides a cleaner framework for analyzing how FDI specifically impacts housing prices, as other confounding factors, such as unchecked speculation, are less influential. Our analysis will focus on the impact of regional employment influxes on nearby housing prices, particularly in Ireland, where such changes (both sales and rental) are driven by the concentration of internationally trading firms (FDI) in urban centers. Job creation by international MNCs should, ceteris paribus, boost housing demand, hence increasing housing prices and land value. This includes direct reactions, such as new worker wages, but indirect effects, “as [the] worker’s wage circulates through the local economy. ”

Figure 1: Housing Prices in Ireland’s Counties 1997-2016 Source: Housing Statistics, Department of Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government. Available at: http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/statistics/housing-statistics.

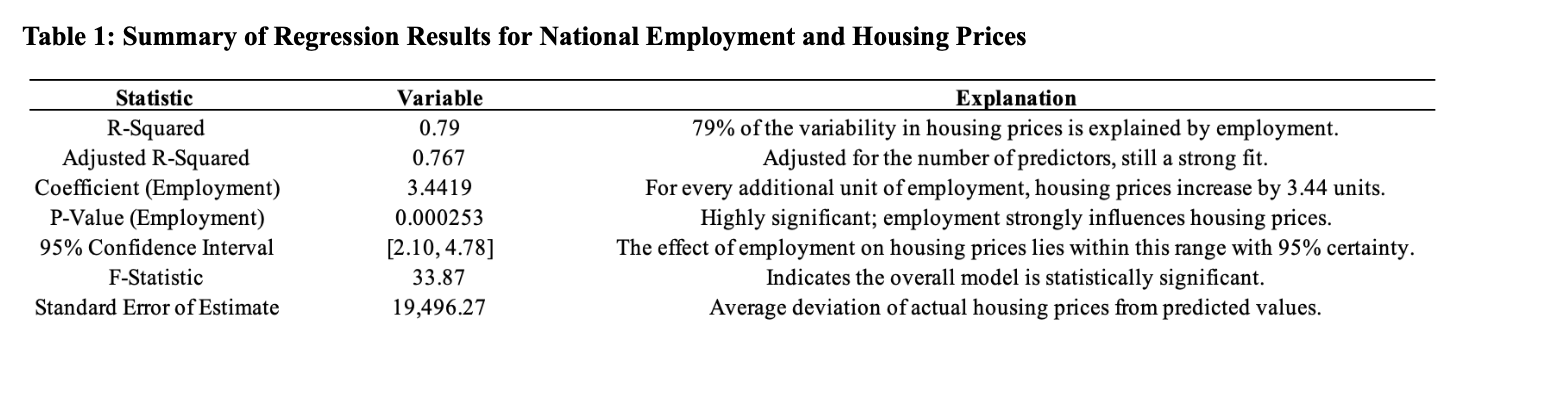

It is additionally crucial to consider the context of housing supply constraints, as they amplify the impact of employment growth on housing prices and provide a clearer framework for analysing the relationship between FDI-driven demand and housing market dynamics. Between 2006-2012, housing construction in Ireland experienced a sharp decline, evidenced by a reduction of commencements as a percentage of housing stock from 4.5% to as little as 0.2%. This contraction disrupted real estate investment and led to a severely constrained housing supply. Over time, even the housing stock net of obsolescence (accounting for homes removed from market due to aging, demolition, or deterioration) experienced a decline. In a stable or growing housing market, employment has two effects: higher housing prices and increased construction activity as demand rises with job creation and higher incomes. However, the collapse of construction during this period suggests that the supply side of the housing market could not respond to said demand. As a consequence, this indicates that the effect of employment growth will be seen primarily through its impact on housing prices. Our analysis will, hence, offer a clearer view of how employment and FDI-driven demand influence the housing market under supply-constrained conditions.

Figure 2: Commencements as Percentage of Housing Stock in Ireland 2004 - 2013 Source: Housing Statistics, Department of Housing, Planning, Community and Local Government. Available at: http://www.housing.gov.ie/housing/statistics/housing-statistics.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) inflows, as measured by official statistics, often fail to accurately reflect the actual economic activities performed by foreign corporations, which are better captured in employment surveys such as the Forfás Annual Report by the Department of Trade and Enterprise (DETE). This discrepancy arises because official FDI data encompasses a wide range of aggregate figures 4and non-tradable activities. For example, it includes financial transactions and services conducted within the Financial Services Centre (FSC) and other non-FSC service sectors that are not directly tied to tangible production or employment generation. These non-tradables typically represent activities such as financial engineering, asset management, or other back-office functions, which, while contributing to the recorded FDI inflows, may have limited impact on job creation or broader economic benefits within Ireland. Consequently, the official FDI inflow data can be misleading if interpreted as a measure of direct economic contributions. In contrast, employment surveys, by focusing on job creation and workforce engagement, exclude non-tangible elements and provide a clearer picture of the real economic impact of foreign corporations. The employment data used in this analysis is sourced from the Department of Jobs, Enterprise, and Innovation’s Annual Employment Survey, covering the years 2004 to 2013. This survey serves as an annual census of employment within all known manufacturing and internationally traded services sectors in Ireland. However, it is not a comprehensive dataset of all employment in Ireland (Lawless, 2012). The survey records employment levels as of October 31st each year and is conducted via postal questionnaires, supplemented by an extensive telephone follow-up. Each firm reports its annual employment figures for the period spanning November 1st of the previous year to October 31st of the current year. It also captures key firm-level details, including sector classification, the number of employees, and whether the firm is majority foreign-owned or Irish-owned.

Figure 3: Total Employment in Foreign Firms 2008-2018

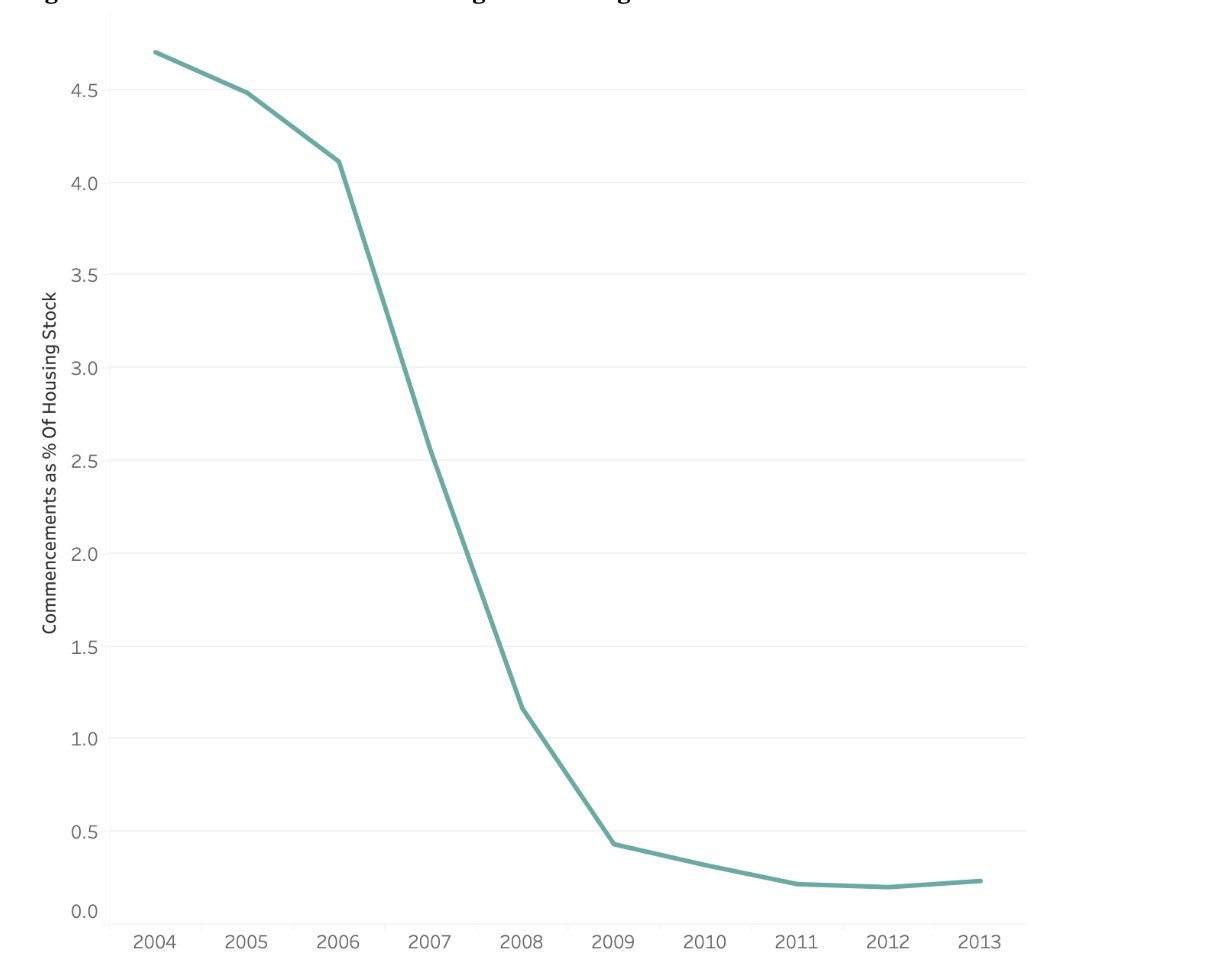

Table 1: Summary of Regression Results for National Employment and Housing Prices

The regression analysis highlights a strong and statistically significant relationship between total employment and national housing prices, underscoring the vital role employment plays in shaping housing market dynamics. The model’s R-squared value of 79% indicates that 79% of the variation in housing prices is explained by employment, with an adjusted R-squared of 76.67% confirming the robustness of this relationship after accounting for potential biases. The F-statistic of 33.87 and a significance F value of 0.000253 demonstrate that the relationship is highly statistically significant, with a negligible likelihood of these results arising by chance. The positive coefficient for total employment (3.4419) suggests that, on average, an increase of unit of job(s) corresponds to a 3.44-unit increase in housing prices, reflecting the demand-driven nature of the housing market. This connection can be attributed to the interplay between job creation and urbanization. Employment growth, particularly in urban centers, attracts workers to economic hubs, driving housing demand and increasing property values. These effects are amplified in regions with high concentrations of foreign direct investment (FDI) and internationally trading firms, where job creation by multinational corporations not only directly impacts local purchasing power but also stimulates secondary economic activity as wages circulate through the local economy. Figure 4: Location of foreign-owned firms, 2004-16 The highest concentration of foreign-owned firms in Ireland is located in the Dublin region. Consequently, we observe a stronger correlation between regional employment levels and housing prices in areas characterized by high levels of FDI-driven employment. Regression analysis confirms this, with a robust positive correlation (R = 0.8647) between employment and housing prices in Dublin. Notably, 74.78% of the variation in housing prices can be attributed to changes in employment levels, underscoring the significant relationship between these variables in urban hubs. This phenomenon can be theoretically contextualized through our previous discussion on the bid-rent gradient and urban economic theory. As Ireland's primary economic hub, Dublin attracts substantial employment in high-paying foreign-dominated sectors such as technology, finance, and pharmaceuticals. The concentration of economic activity in these industries generates elevated demand for housing within the city, resulting in sharper price increases compared to rural or less industrialized areas. The higher correlation observed in Dublin, relative to national trends, reflects the unique urban dynamics where proximity to employment opportunities, infrastructure, and amenities significantly elevates housing premiums. Additionally, constrained housing supply in urban centers, such as Dublin, exacerbates this relationship by amplifying price pressures. This aligns with the discussed theory of agglomeration, which posits that cities serve as focal points for both economic activity and population growth. These dynamics make Dublin a critical locus of both economic productivity and housing market pressures, with significant implications for regional inequality and urban planning policies.

Policy Recommendations

Addressing the dual challenges of sustaining FDI-driven growth and managing housing market pressures is critical for Ireland’s economic and social stability. FDI has fueled job creation and global competitiveness, particularly in urban hubs like Dublin, but the resulting surge in housing demand has strained an already limited supply. There are numerous policy recommendations that our analysis puts forth. The first addresses supply-side constraints. In pushing forward commencement growth, which has stagnated significantly (Fig. 2), the Department of Housing (DOH) can assist by simplifying the planning process by reducing bureaucratic inefficiencies such as nimby-ism (Not In My Backyard), loosening rigid land-use restrictions, and hiring positions for previously understaffed local authority councils. Ireland currently implements rent control measures primarily through Rent Pressure Zones (RPZs), which cap annual rent increases at 2% or the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices (HICP) inflation rate, whichever is lower, in areas of high housing demand. However, enforcement challenges, exemptions for certain properties (e.g., those recently renovated or not rented in the past two years), and limited housing supply constrain the effectiveness of these controls. Improvements could include enhanced enforcement mechanisms to ensure compliance, streamlined planning processes to boost housing supply, and clearer criteria for exemptions to prevent misuse. Establishing a public rent register would increase market transparency, while promoting longer tenancy agreements with graduated rent increases could balance tenant protection with landlord interests. A holistic approach integrating rent controls with broader housing policies—such as incentivizing development, investing in social housing, and aligning with sustainable urban planning—would address underlying market imbalances and ensure long-term affordability for renters. Additionally, public-private housing partnerships (PPPs) involve collaborations such as Build-to-Rent developments, social housing leasing, mixed-tenure projects, and land swaps, which combine public support with private sector efficiency to deliver affordable and social housing. These partnerships can be improved by the DOH by ensuring clearer and more transparent agreements with long-term affordability provisions, offering stronger financial incentives like tax breaks or rental guarantees, and streamlining planning processes to reduce delays. Effective land use policies prioritizing affordable housing on public lands, along with innovative funding models such as shared equity schemes or pension fund investments, can further enhance outcomes. Regular audits, community engagement, and the incorporation of sustainable building practices would also increase accountability, public trust, and long-term benefits, ensuring that PPPs address housing shortages while creating inclusive and livable communities. Lastly, expanding public transportation networks in Ireland is a critical policy recommendation to connect suburban and rural areas to urban economic hubs like Dublin, Cork, and Galway, thereby reducing the housing demand pressures concentrated in city centers. For example, the DART+ Expansion Plan aims to extend suburban rail services to areas such as Drogheda, Maynooth, and Celbridge, improving access to more affordable housing while reducing reliance on car commutes. Similarly, the MetroLink project will establish a high-capacity metro line connecting Dublin Airport and northern suburbs to the city center, significantly improving commuting efficiency. In Cork, the proposed light rail system under the Cork Metropolitan Area Transport Strategy (CMATS) will connect suburban neighborhoods to the city center, complemented by an expanded bus network to support accessibility. Nationwide, programs like BusConnects and Local Link can enhance regional and rural connectivity, enabling workers to live in less expensive areas while commuting to economic hubs. Prioritizing these investments in public transit infrastructure will not only alleviate housing demand in urban centers but also promote balanced regional development, reduce environmental impacts from urban congestion, and create a more sustainable housing market.

Future Outlook

The interplay between FDI, employment, and housing markets in Ireland will evolve amidst global economic and technological shifts, presenting both opportunities and challenges. Increased competition for FDI from emerging markets and changes in global tax policies, such as the OECD’s global minimum tax and post-Brexit dynamics, may affect Ireland’s investment inflows, particularly in sectors like technology and pharmaceuticals. Emerging industries, including renewable energy and biotechnology, could shift FDI focus, requiring Ireland to adapt its workforce and infrastructure. The rise of remote work models may reduce housing demand pressures in urban hubs like Dublin by making suburban and rural areas more attractive for workers. Continued immigration and natural population growth will sustain housing demand, especially in cities, exacerbating affordability challenges unless housing policies are strengthened. Environmental and climate goals will increasingly shape urban planning, with initiatives like Cork’s proposed light rail system and green housing programs addressing sustainability while combating housing shortages. Technological advancements such as modular housing and 3D printing offer potential to alleviate supply constraints, and smart city initiatives may reshape urban living in areas like Dublin. EU integration and compliance with policies on taxation, climate, and housing will remain critical, alongside balancing competitive corporate tax rates with addressing housing inequities. Dublin will likely remain Ireland’s economic epicenter due to its infrastructure and skilled workforce, but affordability and supply constraints must be addressed through coordinated policies to ensure long-term sustainability. Ireland’s ability to manage these dynamics will serve as a model for other small economies, showcasing how to integrate economic competitiveness with environmental and social responsibility.